|

The stories of the Highland Clearances are endless, whether they are individual cases or something that effected whole communities. Although the clearances are associated with the highlands there were other parts of Scotland which suffered as well, like Argyle and Perthshire, not to the same extent as the likes of Sutherland in north east Scotland, but they were cleared never the less. This page endeavors to show just what extent the clearances areas covered, areas which today still suffer the consequences of being depopulated.

By the end of the 18th and the first half of the 19th centuries, the clan system in the Scottish Highlands was nearing the end of its span. Ironically, the deliberate dismantling of the clans, so cruelly started in the bloody years after Culloden, was completed not by the aftermath of glorious rebellion but by the decidedly unromantic process of civil eviction, much if it at the hands of the successors of those same Highland chiefs who had brought out their kin for the Jacobite cause in the first place, oppressed by the situation forced upon them from London.

Landowners, many of them ruined financially by the 1745 Rebellion, saw an opportunity to restore their finances by replacing their tenants with sheep, and so set about clearing their lands of the Highland families and communities who lived there. Not all landowners resorted to this heartless action, but many of those who did carry out their task with ruthless and barbarous efficiency, often through the agency of a factor.

Boreraig

One such individual was Macdonald, factor of the district of Boreraig and Suishnish on Skye, who was also a Sheriff Officer and - ironically - local Inspector of the Poor. In September 1853, with the Sheriff-Substitute and a body of police, Macdonald came to Boreraig and began the removals of the families living there. Most of the men were away working in Glasgow or on the railroads, but some who were attending their cattle in the hills heard the commotion. They came down in haste, and there was a short, brutal struggle, in consequence of which three men - John Macrae, Duncan Macrae and an Alexander MacInnes - were placed in irons and dragged thirty miles to Portree. In their absence, the evictions continued at Boreraig and elsewhere. One lawyer, writing at the time to a newspaper, reported:

The scene was truly heartrending. The women and the children went about tearing their hair, and rending the heavens with their cries. Mothers with tender infants at the breast looked helplessly on, while their effects and their aged and infirm relatives were cast out, and the doors of their houses locked in their faces. No mercy was shown to age or sex, all were indescriminately thrust out and left to perish.

At Portree, the two Macraes and MacInnes were released subject to their promise to appear before the Court of Justiciary sitting in Inverness. Without food or money, they walked to Inverness - a distance of one hundred miles - and there surrendered at the Tolbooth. Their accusers must have thought the outcome of their trial a foregone conclusion, but they were defended by a passionate advocate by the name of Rennie, who persuaded the jury to return a verdict of not guilty.

After the trial, the three returned to their families. They opened the houses, put back the roof timbers and briefly returned to some semblance of normal life, but their victory was shortlived. On 30 December, in the depths of a Highland winter, Macdonald came again when the Macrae men were away. The mother of John Macrae, who was eighty-one, refused to move from her bed and was dragged out on her blanket. The houses were boarded up and the people - children, women and old folk alike - were left outside in the snow to survive as best they could.

At this remove, it is difficult to imagine the inhumanity of the Clearances. The story told here of the evictions of the Macraes of Boreraig is just one among thousands. Of those evicted, many died of starvation and exposure, while others were reduced to living outside like animals, surviving on Parish Relief and the charity of others. Many Highlanders emigrated or took service with the British army, which in large measure accounts for the wide scattering of Scots around the world today.

|

|

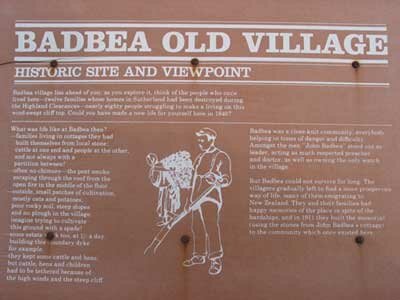

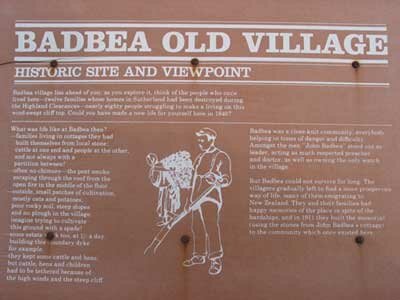

Badbea

Badbea is on the East coast of Caithness, about five miles North of Helmsdale. When the Straths of Langwell, Ousdale and Berriedale were cleared for the establishment of sheep farms, evicted tenants settled in Badbea and hacked out plots of land on the steep hillside.

Badbea is a secluded desolate spot situated on the slopes leading down to the precipitous Berriedale cliffs.

In 1814 the Estate was sold to James Horne and the population numbered around 80 people comprising of 12 families.

The families were industrious and frugal. Every house had its spinning wheel; spinning and carding were learnt by all the young women.

|

|

|

Each family possessed a few head of cattle, a fat pig and an abundance of fish and plenty of good potatoes and milk. Fresh water was obtained from a spring flowing out of the hillside.

Life was hard and very primitive, especially with only one horse in the whole village. There was not even a plough and the chaib (a kind of spade) was used in its place. The harrow was dragged behind a man, and the manure carried on women’s backs in creels.

Fishing was the main employment. Tons of fish could be landed in a day with fish put aside for the widows with young children.

At one time there were 13 fishing boats at Berriedale, which would go out and fish for herring. Women would tether their children and chickens to the rocks while they spent their days gutting the fish, unfortunately, Donald Horne decided to do away with herring fishing for salmon fishing and so another form of employment was gone.

There was some trifling work to be got occasionally on the estate, but the rate of wages was very low. If any young man had the courage to go and work beyond the estate his parents would suffer by being turned out of their house.

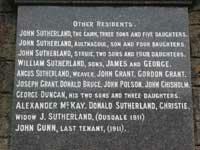

The monument was erected in 1911 by Donald Sutherland in memory of the people of Badbea including his father, Alexander Sutherland, who was born in Badbea in 1806 and emigrated to New Zealand in 1839. Also listed are the names of some of the other inhabitants of the village. Many emigrated to New Zealand and North America, the last inhabitant leaving in 1911.

|

|

Coigeach

An area which must be mentioned is Coigeach, the crofters gave stout resistance, where the women disarmed about twenty policemen and sheriff officers, burning the summonses in a heap, throwing their batons into the sea and ducking the representatives of the law in a neighbouring pool. The men formed the second line, just in case the wimen received ill treatment, this had to be the case as the tenancy agreement would have been signed in the man’s name. The men never needed to get involved and the officers of the law returned home without serving any summonses for evictions. The proceedings of the Coigeach crofters came to the ears of the noble proprietor, with the result the Coigeach tenants are still where they are and today are among the most comfortable crofters in the North of Scotland. Perhaps a lesson to be learned from this.

|

Croick

In 1845 the people of Glencalvie were evicted off the land their families had lived on for generations. Eighteen families, 88 people, lived in Glencalvie in turf cabins, growing barley and oats, herding cattle and sheep on a total holding of no more than 20 acres. The most incredible rent, almost four times what a farmer in England would pay for the same land, was paid for this land for generations without arrears, except for some weeks during the famine in 1836. Of the 400 to 500 inhabitants cleared 90 or so people had nowhere to go and took shelter in the churchyard of Croick Kirk.

Their plight was reported in the Times. [See Documents and Letters ] |

Glenelg

As other articles may relate, the tenants of the various MacDonnell chiefs of Glengarry, experienced many waves of removals. As the MacDonnells' debts mounted they sold off more and more of their property until all that remained for the 16th chief, Aeneas MacDonnell, was the Knoydart peninsula. In 1852, after his death, his widow, Josephine, decided, with her factor, Alexander Grant, to clear the land of people in preparation for its sale to James Baird. The remaining tenants lived almost exclusively in the coastal townships of Airor, Dounde, Inverie and Sandaig and, so, did not even stand in the way of sheep being introduced inland. An impoverished population, though, might mean a contribution from the landowner to the Poor Relief fund so they had to go.

|

Glen Loth was cleared at the same time as nearby Kildonan, in three waves in 1809. 1813 and 1819. Across the county to the west, Strathnaver was burning. The recent biography of Patrick Sellar, who ruthlessly cleared these glens and town-ships, has a lot to say about the clearance of Glen Loth. [See main oppressors for more on Patrick Sellar] |

|

Late afternoon in Glen Loth

The distribution of the clans

Mr Dennis MacLeod. had recently conducted an exercise to establish the distribution of the clans in the period immediately prior to the clearance of the Strath of Kildonan 1813-1819.

The method he has used is to compare the number of entries recorded in the Kildonan parish register for each clan over the period 1795 to1815 with regard to births, deaths and marriages. While this method is not as absolute as a census in determining relative numbers, it is nevertheless reasonably accurate because of the large number of entries (1400). The number of entries should not be confused with population numbers which were probably about the 2000 level.

From the distribution numbers (see Table below) it can be seen that the Sutherlands and their affiliate Gordons make up 24% followed by the Mackays and their sept Polsons at 20%. The Gunns and Bannermans are also prominent at 13% and 7% respectively, followed by the Mathesons, Macleods and Macbeths. It is interesting to note that Highland clans comprise over 99% of the entries, the Gilchrists being the exception.

Number of Entries by Clan in the Parish Register for Kildonan in the Period 1795 to 1815

|

|

Clan (1)

|

No. of Entries (2)

|

Distribution (%)

|

|

Sutherland

|

235

|

16.8

|

|

MacKay

|

188

|

13.5

|

|

Gunn

|

179

|

12.8

|

|

Bannerman

|

101

|

7.2

|

|

Gordon

|

97

|

6.9

|

|

Polson

|

89

|

6.4

|

|

Matheson

|

71

|

5.1

|

|

Macleod

|

58

|

4.1

|

|

Macbeth

|

58

|

4.1

|

|

Murray

|

44

|

3.1

|

|

Ross

|

43

|

3.1

|

|

Fraser

|

35

|

2.5

|

|

Grant

|

34

|

2.5

|

|

Macdonald

|

28

|

2.0

|

|

Bruce

|

28

|

2.0

|

|

MacIver

|

24

|

1.7

|

|

Macpherson

|

24

|

1.7

|

|

Munro

|

17

|

1.2

|

|

Others(3)

|

46

|

3.3

|

|

1399

|

100.0

|

|

|

(1) Including all spelling variations.

(2) Comprised of births, deaths and marriages.

(3) Including, in descending order; Campbell, Henderson, Gilchrist, Stewart, Mackenzie, Macintyre, Macintosh, Nicol and Macnicol; and with single entries for Keith, Sinclair, Robertson, Cuthbert, Gray, Chisholm and Mowat.

Helmsdale

In the early 19th Century almost all of the inland settlements in this part of Scotland were cleared and the habitants made their way to coastal settlements, such as Helmsdale, this was in preference or an alternative to being shipped to the colonies or to North America. The aim was to create a community able to live from both fishing and farming, and, in particular to take advantage of the herring boom then in full swing. As you look around Helmsdale's harbour today, try to imagine it as home port for up to 200 herring boats.

People had always been leaving Helmsdale. Many emigrated without a trace. Sometimes, however, people left in such numbers that their departure did not go unnoticed. This was true of the emigrations of the 1730s and 1770s. Relatively few people, however, emigrated during the Clearances, that is in relation to the great numbers of families moved from the interior to the coast (on the Sutherland Estate between 1807 and 1822).

|

Between 1829 and 1832 the south and east of the county of Sutherland was gripped by an emigration fever. Population had continued to grow but there had been a deterioration of living standards. Cattle prices had fallen after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and other sources of income had diminished. Agricultural holdings were very small - a direct result of the resettlement policy pursued by landlords. Some people did become successful fishermen, but the opportunities were limited. Many only survived through the earnings from seasonal work in the south. For landless families or cottars, in particular, life could be very difficult. |

In such circumstances, the 'pull' of extensive land overseas, emigration agents, and the existence of a 'chain', linking Highlanders with friends and relatives abroad, all operated to set emigration in motion. The particular trigger for the phase of emigration from Sutherland in 1829 appears to have been encouragement given by some who had gone out earlier to go to Zorra in what was then Upper Canada, now Ontario.

Helmies (The name for those born & bread in Helmsdale) continue to leave the village and the surrounding area even to this day, this section is dedicated to those who settled elsewhere in the world. [See Emigrants and emigration for individuals or families]

Strathconnon

From 1840 to 1848 Strathconnon was almost cleared of its ancient inhabitants, to make room for sheep and deer, as in other places. Forestry plantation was becoming extensive as well, thousands of acres being affected. The property around Strathconnon was under trustees when the harsh proceedings commenced by the factor, Mr Rose a notorious Dingwall solicitor. He began by planting trees on the extensive hill pastures, taking away grazing land which had been there for generations, then evicting from arable land leaving the people with no means of being self sufficient and independent. It has to be added that like other places, none of the tenants were in arrears.

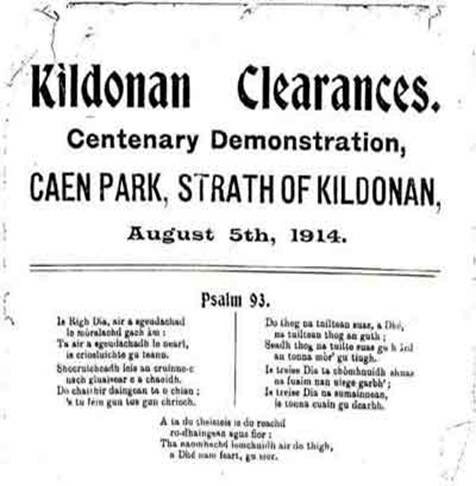

The Strath of Kildonan

A long a and lovely glen winds from Helmsdale, on the east coast of Sutherland, to the bleak settlement of Kinbrace 18 miles inland, and on another five miles to Loch Badanloch, the source of the Helmsdale River. Heading northwest up the strath, once you have left the outskirts of Helmsdale behind there is barely a handful of inhabited houses until Kinbrace comes in sight. It was not always so. Kildonan was savagely cleared in the years between 1813 and 1819 - so savagely that these clearances provoked the first recorded dissent against the evictions anywhere in the Highlands. The clans here were Gunns, Mathesons, Mackays, Macbeths and Sutherlands - all the peoples of the Sutherland/Caithness border region, but Kildonan was predominantly Gunn territory, and it was the Gunns who resisted in 1813. They first ran off a Mr Reid, agent for some southern sheep-farmers, who had visited the strath, asking questions and taking notes; Mr Reid declared to anyone who would listen that he had been attacked by a mob and had barely escaped with his life. It was just an excuse the Duke of Sutherland’s factors had been praying for. The male staff of the estate were sworn in as special constables and a detachment of infantry sent out at the double from Fort George. This was more than the Gunns could withstand and their resistance melted away. Within three months large areas of upper Kildonan had been entirely cleared, and the people offered tiny allotments of poor land on the cliff tops near Helmsdale, or sent into exile in Canada - the choice of many of the younger people. In June of the year they sailed from Stromness in Orkney, bound for the Red River settlement in Ontario.

|

|

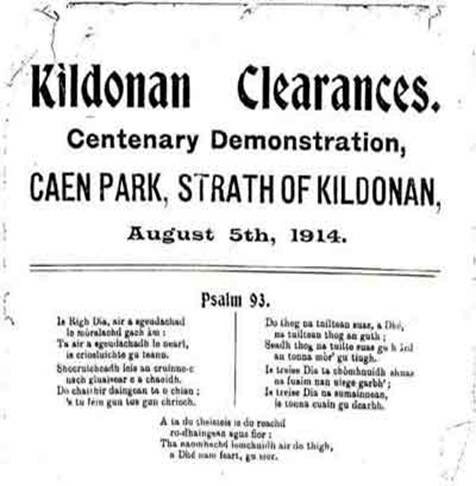

The clearances psalm sheet....

Copy supplied by Kenny Mackenzie (red kenny the plumber)

This sheet belonged to a George Munro of Navidale (kenny's great grandfather) who happened to be the Precentor that day.Shortly after the event "Toffs" came down with their "keepers" and removed all his papers photos etc. for burning. George had kept this order of service within a zipped bible and he challenged the intruder with the words "if you dare burn that bible you are really in trouble" this was enough to frighten him off , and so the bible was handed down to his son Angus who in turn gave it to Kenny in 1950.......

Sutherland

Remote and undeveloped, a land of moor and mountain, with tiny patches of arable land like islands in a vast sea of heather, the county of Sutherland is located in the far north of Scotland. Once the land of the powerful and dominating clan Mackay, most of the people still carried the name at a time when the clan system had suffered a death.

Between 1812 and 1819, thousands of people were evicted from their holdings and dwellings to make room for sheep. Few subjects under the realm of Scottish history hold so much controversy and blood-feeling as the Sutherland Clearances. Special focus can be made on the Sutherland Clearances as they were probably the most ruthless; the disastrous change which was a major factor in the region was the marriage of Elizabeth, Countess of Sutherland to the English Lord, George Granville Leveson-Gower. [See main oppressors]

With various titles behind his name he eventually became the 1st Duke of Sutherland. Coming from England he thought that Sutherland was very rough compared to what he was used to, so with all his wealth he set about changing everything from the people to their homes regardless that their ancestors had lived and worked on the land for centuries undisturbed.

The humble dwellings were of the peoples own rearing as was the waste land which they turned into good arable and grazing land. These were lands which they had defended against the invader who had found only a grave. Their young men now fighting in foreign lands fighting in battles at the command of their chieftain the battles of another country, England , not in the character of hired soldiers, but men who regarded these very holdings as their stake in the quarrel. To them Stafford’s adopted scheme was fraught with the most monstrous injustice, the Sutherland clearances were also some times known as 'the cruel clearances' because of the harsh treatment which took place. The reality of the highland clearances could be seen all over Sutherland. The remains of burned out blackhouses, frequently comprising of whole villages and settlements, standing as witnesses to the cruel and uncompromising plans drawn up by men driven by greed. From Strathnaver to Assynt many thousands of people were moved from their ancestral lands to emigration ships bound for the colonies or to the difficult and rocky terrain of the coast. A numerous party of men would enter a district, with a factor at the head; they would pull down houses over inhabitants’ heads so that no human dwelling would be left standing. To prevent any temporary re-erection, the wreck would even be set on fire. In one day the people were deprived of home and shelter, and left exposed to the elements. Many deaths are said to have ensued from alarm, fatigue, and cold. Families were pushed as far to the coast as humanely possible, one man named MacKay, whose family lay ill with fever outside their burnt dwelling was forced into carrying two of his sick children 25 miles to the coast only to try and find what shelter they could find. This could be perhaps between the rocks on the sea shore, a cave if they were lucky, but most likely they would have ended just out in the open exposed to the elements.

James Kinloch, General Agent of the Sutherland Estates published an account in 1821 regarding the improvements. [ See letters and Documents]

What Stafford was effectively doing was changing the way of peoples lives in its entirety, when they had lived a simple ordinary life for generations. Men who were considered to have zeal, foresight and prudence were considered for principal tacksmen jobs or working under them as special constables and the likes. Out of the twenty nine principal tacksmen on the Sutherland estate, seventeen were natives to Sutherland, four from Northumria, two from the county of Moray, two from Roxburghshire, two from Caithness, one from Midlothian and one from Merse. These jobs were considered to be in similar fashion to a chief with those respecting him that worked under him. The unfortunate ones were the wimen, who bore the burden of the outdoor work, as men no longer deemed such an occupation unworthy of them. Such were the changes that many rather than adopt them decided to sacrifice their customs and leave the homes of their ancestors. It basically cost them nearly the same effort to remove from the spot they were born and brought up to a place and a dwelling which was situated at the sea shore as it would have been in exertion transporting them selves across the Atlantic. The cost of moving took its toll with livestock as well on account of winter keep, to an extent of the all the calamity in the spring of 1807 there died in the parish of Kildonan alone, two hundred cows, five hundred head of cattle and more than two hundred small horses.

It is well know that the borders of Scotland and England were inhabitated by numerous populations, who, in their pursuits, manners and general structure of society bore considerable resemblance to that which existed in the Highlands of Scotland.

When the Union of the Crowns rendered the maintenance of that irregular population unnecessary, the people were removed and the mountains were covered with sheep. It proved suitable for this species of stock with low maintenance. Taking example from experience the highlands were calculated for the same purposes. As it was, evictions took place from Glen to Glen through out leaving only the ruined remains to be seen.

|

Skye and the Battle of the Braes

On the island of Skye, the cruelty of the clearances and the disregard for human life and values festered in the minds of the people for many years until eventually the worm began to turn.

Those crofters remaining at the time were denied access to Ben Lee to graze their stock. Although the crofters had agreed to pay a generous rent at the expiry of the old lease, the tenancy was let to the sitting tenant. In the face of this injustice, the crofters decided to go ahead and graze their stock regardless, some even refusing to pay rent until the problem was resolved.

|

|

|

Lord MacDonald decided to have the leaders evicted, but when the authorities moved to carry out the order, the Braes people demanded that the documents be burnt. Against this insurrection, 50 extra police were dispatched to Skye. As they reached Braes, the crofters launched at them with whatever missiles they could find. A number of crofters were taken prisoner, convicted and fined. (Some versions of this story say that not a blow was struck by the crofters before the arrests were made, and that the police baton charged through the crowd, inducing the riot).

The government, weary both with the demands of arrogant Highland proprietors and the agitation of the crofters, was at last stung into action, and a commission of enquiry was set up to investigate "the conditions of the crofters and cottars in the Highlands.... and everything concerning them." It had wide powers to call witnesses, demand any document, and to visit any place deemed necessary in order to obtain the fullest possible information. Starting in 1883 the commissioners travelled widely among the Highlands and Islands, interviewing hundreds of witnesses, both crofters and landlords. In April 1884 they made their report, less than a year after they had carried out their first interviews in Skye.

Though the Napier Commission's recommendations were less sweeping than some of the crofters had hoped, there was much they could be pleased with. London was slow to act, however, and there was further trouble and more rent-strikes on Skye, to the extent that the Government felt it necessary to send ships and around 400 marines to keep order. Four out of five Highland Members of Parliament were now committed to land reform, and the Liberal Government's slim majority gave them bargaining power. In 1885 the Crofters Act was passed through Parliament, and brought the crofting community substantial benefits. For the first time they had security of tenure, and this could be passed on to another family member. They had the right to compensation for any improvements they carried out, and a Land Court was set up to fix fair rents. It had taken over a hundred years of evictions and banishments, grief and separation, and finally anger and rebellion, but at last the remaining Highlanders had a right to a life in their own country.

Whitsun In 1807, at Whitsun, 90 families in the parish of Farr and Lairg were evicted. Their crops were left on, or in the ground, and they had to leave carrying as much possessions as they could: furniture, roof timbers for their new dwellings. If they could find no shelter or build a rudimentary one they slept in the open – women, children, old and sick alike.

|

Back to Top

|